Geocentrism

Geocentrismul este o teorie cosmologică (sau model de fizică cerească) azi abandonată. A fost primul sistem și concepție astronomică al multor civilizații antice, cum sunt grecii, evreii, romanii, egiptenii și babilonienii, asirienii și perșii, această uranografie[1] predominând ca explicație general acceptată până în secolul al XVI-lea[2], când a fost lent și gradual înlocuită cu diverse modele heliocentrice, printre care și cel care este azi prevalent.

Deși geocentrismul a fost modelul predominant în Antichitate, el nu a fost și unicul, cel puțin în cazul grecilor existând și înțelepți care au pledat pentru modelul heliocentric. Aristarh este exemplul cel mai cunoscut.

O posibilă explicație a faptului că modelul geocentric a fost adesea și primul propus și în același timp a rămas preponderent milenii, e că pentru toți observatorii Soarele și planetele păreau a se roti în jurul Pământului, în timp ce observatorul constata că Pământul rămânea static. Fără un punct de referință exterior, o concluzie similară trage chiar și azi, de exemplu, un pasager aflat într-un vagon de tren tocmai pus în mișcare, și care nutrește un timp falsa impresie că de fapt trenul de pe linia alăturată a început să se miște. Singura excepție de la regula primordialității clare a unui sistem geocentric este cel al civilizației grecești, unde ideile geocentrice (Pitagora, Platon, Aristotel) au apărut relativ simultan cu cele heliocentrice (Filolaus, Icetas, Aristarh).

Modelul geocentric a fost uneori asociat cu teoria Pământului plat, însă grecii au abandonat devreme această idee, de prin secolul VI î.e.n., grație lui Pitagora[3] Alții, precum evreii de exemplu, au păstrat această asociere între geocentrism și ideea de Pământ plat, așa cum se mai poate constata și azi în Scripturile evreiești[4] și creștine.[5][6] Astfel cosmologia pe care o găsim în Biblie descrie un Pământ plat peste care se întinde un vast “firmament”, adică un imens tavan rigid; etimologia termenului firmament însăși sugerează, atât în românește cât și în ebraica biblică, natura sa rigidă, Facerea vorbind despre o "tărie" numită de Dumnezeu cer (vezi de exemplu Facere I, versetele 6, 7 și 8).[7] Acest tavan avea rolul separator, adică de a ține "apa cosmică" să nu cadă pe pământ (Facere 1:6-8), avea formă de cupolă și era sprijinit pe crestele munților. Avea găuri sau fante dotate cu capace (Facere 7:11) care permiteau uneori apei de deasupra să cadă sub formă de ploaie pe pământ. Proverbe 8:31 vorbește de rotocolul pământului sugerând clar că este vorba de forma rotunda. Firmamentul era în același timp și suportul pe care Dumnezeu a pus Soarele (Psalmi 19:4) și stelele (Facere 1:14) în cea de-a patra zi a creației. Evreii mai credeau că pământul, de formă plată fiind, plutește pe o altă imensă cantitate de apă (Facere 1 :7) și că în timpul miticului Potop al lui Noe aceste oceane s-au unit pentru a-l acoperi.[8][9][10][11][12]

Urmând Biblia și atmosfera culturală elenistică a epocii lor, Sfinții Părinți ai Bisericii Creștine Timpurii au împărtășit și ei ideile geocentriste, așa cum se poate constata, de exemplu, din scrierile Sfântului Vasile cel Mare.[13][14] Sfântul Ioan Gură de Aur, nu avea nici el o concepție diferită de aceea biblică, așa cum se poate constata din a 4-a sau a 12-a sa omilie[15][16], după cum și Sfântul Grigore de Nazianz avea și el o opinie tot în conformitate cu sugestia Scripturii[17], ca și Grigore de Nyssa.[18]

Sfântul Ioan Gură-de-Aur, literalist convins[19], împărtășea integral concepția biblică despre lume, fiind convins că Pământul este nu numai static și situat în centrul lumii, ci și plat, plutind pe ape.[20][21][22] Părintele Lactanțiu (sfetnicul Sfântului Constantin cel Mare și profesorul fiului lui) a scris violente pagini contra celor care considerau că Pământul este rotund[23], la fel ca și Sfântul Ieronim[24], care și el credea și promova ideea Pământului nu numai aflat în centrul Universului (geocentrism), ci și ideea de origine biblică[25] că Pământul este plat; astfel de idei va manifesta în aceeași epocă și călugărul bizantin geograf Cosmas Indicopleustes, și nici măcar Isidor din Sevilia nu poate fi exclus dintre adepții Pământului plat, căci deși era un teolog care dispunea de numeroase surse păgâne, va compila enciclopedii pe baza lor rămânând prea confuz în chestiunea sfericității Terrei, pentru a putea trage azi o concluzie certă[26]. De altfel, Sfinții Părinții ai bisericii creștine timpurii nu s-au înșelat atunci când au interpretat Biblia ca fiind o scriere a cărei cosmologie este geocentrică și a cărei opinie despre forma Pământului este că acesta este plat, întrucât înțelepții iudaismului care au interpretat și ei Biblia (evreiască) de-a lungul timpului, n-au ajuns deloc la o concluzie diferită.[27]

Cosmologia greacă

modificareCosmologia greacă geocentrică este cea mai importantă din mai multe motive; în primul rând ea a influențat cultura europeană pentru mai bine de 2 milenii, până când în sec. al XVI-lea în Occident au fost propuse cu succes noi modele heliocentrice. În al doilea rând, ea e importantă pentru că a reușit să influențeze chiar și cosmologia biblică creștină, a Noului Testament, care părăsește opinia veterotestamentară a cosmosului format din 3 entități, pentru a împrumuta complicata structură cerească tipică gândirii grecești.[28] În al treilea rând, în ciuda falsității ei, această cosmologie geocentrică se perfecționa continuu și dădea cont de cea mai mare parte a observațiilor empirice, în contrast cu versiunile heliocentrice, care erau respinse din pricina incapacității lor de a explica lipsa fenomenului de paralaxă.[29]

Primii filozofi greci precum Thales, Anaximandru și Anaximene (“cei 3 cosmologi”, cum sunt ei cunoscuți - Mircea Florian, 1922). Considerau Pământul a fi plat și fix, restul corpurilor cerești cunoscute rotindu-se în jurul lui.

Pitagora și (cei mai mulți dintre) discipolii săi imaginează o cosmologie originală, în care Pământul este deja rotund, nu se află în punctul central de rotație al planetelor (nu e un model heliocentric), în acest punct special aflându-se imaginarul și invizibilul “foc central” (Mircea Florian, Îndrumar de Filosofie, 1922, reeditat Humanitas 1992), în jurul acestuia rotindu-se planetele și Pământul, plus “sfera stelelor fixe”, plus o altă planetă imaginară, Antipământul.

Platon are o cosmologie încă și mai fabuloasă și mitică, Pământul (rotund) aflându-se în centru, static, planetele fiind extrem de aproape de el, iar stelele la o distanță de asemenea mică (~10 diametre terestre), toate rotite de zeițele destinului. Discipolul lui Platon Eudoxus din Knidos va fi cel care, păstrând viziunea platoniciană, va repune accentul pe perfecțiunea sferelor (sau cercurilor) pe care evoluează în mișcarea lor în jurul Pământului planetele, reluând o idee dragă sectei pitagoreice.

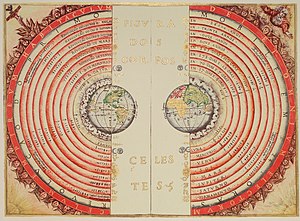

Pentru Aristotel, un alt elev al lui Platon, Pământul se afla în centru, sferele pe care se rotesc planetele și Soarele sunt transparente (din cristal), solide și concentrice; acest sistem încă simplu nu putea explica mișcarea planetelor în toată complexitatea ei, ratând să dea cont, de exemplu, de mișcările retrograde, în consecință Aristotel a trebuit să-l complice adăugându-i mișcări de rotație suplimentare, și astfel sfere de rotație suplimentare. Aristotel ajunge să explice astfel mișcarea a 6 planete postulând existența a nu mai puțin de 55 de sfere! Această "soluție" a complicării excesive a geocentrismului pentru a răspunde printr-un baroc puțin verosimil la ceea ce rata în forma lui originală și simplă, va rămâne un handicap permanent al modelului ptolemaic până la abandonare.

Modelul aristotelician este perfecționat de Iparh (Hiparh) și alții, care introduc modelul cu epicicluri; modelul la nevoie mărește numărul de sfere de rotație la mai mult de două pentru explicarea traiectoriei unui singur corp ceresc (la câte se limitase Aristotel), și a fost cunoscut pentru un mileniu și jumătate sub numele de ptolemeic, după numele lui Ptolemeu, un autor scriind în secolul II e.n., care în Megali Sintaxis a sistematizat toată astronomia greacă[30], aplicând teoria epiciclurilor la toate planetele cunoscute, la Soare și la Lună (Encicl. Britannica). A făcut-o la timp, întrucât curând libertatea de a specula pe tema astrelor va fi drastic îngrădită de creștinismul ajuns religie de stat, interesul însuși pentru fizică migrând înspre metafizică[31]

Modelul geocentric va rămâne în grația autorităților și a publicului larg până când Nicolaus Copernic va propune în secolul al XVI-lea alternativa heliocentrică.

Geocentrismul contemporan

modificareAzi geocentrismul a încetat să mai fie o teorie științifică, însă e departe de a fi dispărut: în SUA și în alte țări există diverse mișcări care, în general din motivații religioase, mai susțin încă veracitatea teoriei geocentriste. Unul din cinci americani crede că Soarele se rotește în jurul Pământului.[32] În România postcomunistă aproape un român din doi crede că Soarele se rotește în jurul Pământului.[33]

Note

modificare- ^ uranografie = imagine a domeniului ceresc. ("ouranography": image of the heavenly realm - The Early History Of Heaven, J. Edward Wright, Oxford University Press 2000, p. VIII, Preface)

- ^ sistem geocentric = orice teorie a structurii sistemului solar (sau universului) în care se consideră că Pământul se află în centru. Cel mai elaborat sistem geocentric a fost acela al lui Ptolemeu din Alexandria, care a fost acceptat în general până în secolul al XVI-lea, după care a fost înlocuit de modele heliocentrice precum cel al lui Nicolaus Copernic. (geocentric system: any theory of the structure of the solar system (or the universe) in which Earth is assumed to be at the centre of all. The most highly developed geocentric system was that of Ptolemy of Alexandria (2nd century ce). It was generally accepted until the 16th century, after which it was superseded by heliocentric models such as that of Nicolaus Copernicus - Encyclopaedia Britannica online)

- ^ La originea ideii sfericității Pământului se consideră în general a fi fost Pitagora și discipolii lui, care au judecat că dacă Luna și Soarele sunt sferice, Pământul trebuie să fie și el la fel. (Credit for the idea that the Earth is spherical is usually given to Pythagoras (flourished 6th century bc) and his school, who reasoned that, because the Moon and the Sun are spherical, the Earth is too. Notable among other Greek philosophers, Hipparchus (2nd century bc) and Aristotle (4th century bc) came to the same conclusion. - Encyclopaedia Britannica online, Determination of the Earth’s figure)

- ^ "Din ce se cunoaște din religia Orientului apropiat al Antichității, putem constata că Biblia reflectă diverse aspecte ale culturii mesopotamiene. Structura fizică a universului așa cum este el schițat în Facere, e similar cu ce se găsește în literatura levantină (a Orientului apropiat): Pământul este conceput ca un disc subțire plutind pe oceanul care-l înconjoară; cerurile sunt o cupolă care ține apele înaltului să nu cadă; sub pământ se află imperiul morților. Ca și zeii literaturilor antice, dumnezeul Israelului este conceput de manieră antropomorfică. Ca și alte popoare, israeliții acceptau magia (Ieșire 7:9-12), admiteau puterea binecuvântărilor și blestemelor (Numeri 22-24) și credeau că voia lui Dumnezeu poate fi cunoscută prin vise, zaruri și oracole." - "Judaism - History, Belief And Practice", Dan Cohn-Sherbok, Routledge 2003 (Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group), Part 1 ("History"), Chapter 2 ("The Bible and Ancient Near Eastern civilization"), p. 9-11.

- ^ Universul egiptean era imaginat în linii mare ca și cel babilonian, anume ca o cutie dreptunghiulară orientată pe axa nord-sud și cu o suprafață ușor concavă, Egiptul aflându-se în centru. O bună idee despre similara stare primitivă a astronomiei ebraice ne putem face citind azi Biblia, de exemplu povestea creației în Facere sau diverșii psalmi care glorifică firmamentul, stelele, Soarele și Pământul. Evreii credeau că Pământul este o suprafață aproape plată, formată dintr-o parte solidă și una lichidă, cerul fiind domeniul luminii unde se mișcă corpurile cerești. În opinia lor, Pământul stătea pe o temelie solidă drept pentru care nu putea fi mișcat decât de către Dumnezeu (ca de exemplu într-un cutremur). (The Egyptian universe was substantially similar to the Babylonian universe; it was pictured as a rectangular box with a north-south orientation and with a slightly concave surface, with Egypt in the center. A good idea of the similarly primitive state of Hebrew astronomy can be gained from Biblical writings, such as the Genesis creation story and the various Psalms that extol the firmament, the stars, the sun, and the earth. The Hebrews saw the earth as an almost flat surface consisting of a solid and a liquid part, and the sky as the realm of light in which heavenly bodies move. The earth rested on cornerstones and could not be moved except by Jehovah (as in an earthquake). According to the Hebrews, the sun and the moon were only a short distance from one another. - How to cite this article: MLA (Modern Language Association) style: "Cosmology." Encyclopedia Americana. Grolier Online, 2012. Author: Giorgio Abetti, Astrophysical Observatory of Arcetri-Firenze.

- ^ "Imaginea Universului în textele talmudice plasează Pământul în centrul creației cu cerul fiind o semisferă care-l acoperă. Pământul este adesea descris ca un disc încercuit de apă. În mod remarcabil, speculațiile metafizice și cosmologice nu trebuiau cultivate în public și nici nu trebuiau așternute pe hârtie, ci fiind considerate secrete ale Torei, erau ferite de transmiterea lor mulțimii. […]" - Topic Overview: Judaism, Encyclopedia of Science and Religion, Ed. J. Wentzel Vrede van Huyssteen. Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2003. p477-483. Hava Tirosh-Samuelson). (The picture of the universe in Talmudic texts has the Earth in the center of creation with heaven as a hemisphere spread over it. The Earth is usually described as a disk encircled by water. Interestingly, cosmological and metaphysical speculations were not to be cultivated in public nor were they to be committed to writing. Rather, they were considered as "secrets of the Torah not to be passed on to all and sundry" (Ketubot 112a). While study of God's creation was not prohibited, speculations about "what is above, what is beneath, what is before, and what is after" (Mishnah Hagigah: 2) were restricted to the intellectual elite.)

- ^ Termenul "firmament" denumește atmosfera între domeniul ceresc și Pământ (Facere 1:6-7, 20) unde are loc mișcarea aștrilor (Facere 1:14-17). Poate fi folosit ca sinonim pentru ceruri (Facere 1:8; Ps. 19:2). El este parte a structurii cerești, fie că e considerat a fi echivalentul "cerurilor", fie că este structura care separă cerul de Pământ. […] Evreii Antichității foloseau de asemenea și alți termeni pentru a descrie cum a creat Dumnezeu cerurile, și bazându-mă pe această colecție de termeni specifici, sugerez că vechii evrei aveau două idei fundamentale despre compoziția împărăției cerești. Prima idee este legată de forma tărâmului ceresc: cerurile sunt un vast acoperiș cosmic. Verbul folosit pentru a descrie metaforic cum Dumnezeu a întins acest imens baldachin cosmic peste Pământ este "nătăh", care înseamnă "a întinde": "Eu am făcut pământul și omul de pe el Eu l-am zidit. Eu cu mâinile am întins cerurile și la toată oștirea lor Eu îi dau poruncă." (Isa. 45:12). În Biblie acest verb este folosit pentru a descrie întinderea (ridicarea) unui cort. Întrucât pasajele care menționează întinderea cerurilor sunt inspirate de simbolica tipică a creației, se pare ca metafora vrea să ne sugereze că cerurile sunt cortul cosmic al lui Dumnezeu. Ne putem azi imagina cum vechii evrei privind în sus spre stele comparau bolta cerească cu acoperișul corturilor în care trăiau; dacă cineva privește în timpul zilei în sus, la acoperișul unui cort în care există mici găuri constată similaritatea cu bolta cerului în timpul nopții. A doua idee a evreilor vechimii în ce privește regatul cosmic este aceea de material solid, referindu-se deci la compoziția lui materială. Termenul răqîa, tradus în mod uzual firmament, indică întindera aflată deasupra Pământului. Rădăcina "rqa" înseamnă a forja, a lovi și deforma un obiect prin șocul cu un alt obiect masiv (greu). Ideea de soliditate și suprafață forjată se potrivește bine cu Ezechiel I, unde tronul lui Dumnezeu stă pe răqîa (tărie, firmament). Facerea I ne spune că firmamentul ("răqîa") este sfera corpurilor cerești (Facere 1:6-8, 14-17; conform ben Sira 43:8). Se prea poate că unii și-au imaginat că pe suprafața solidă a firmamentului (tăriei) se rostogolesc corpurile cerești în călătoria lor aparentă de-a lungul cerului. (“The term "firmament" (רקיע - răqîa') denotes the atmosphere between the heavenly realm and the earth (Gen. 1:6-7, 20) where the celestial bodies move (Gen. 1:14-17). It can also be used as a synonym for "heaven" (Gen. 1:8; Ps. 19:2). This "firmament is part of the heavenly structure whether it is the equivalent of "heaven/sky" or is what separates it from the earth. […] The ancient Israelites also used more descriptive terms for how God created the celestial realm, and based on the collection of these more specific and illustrative terms, I would propose that they had two basic ideas of the composition of the heavenly realm. First is the idea that the heavenly realm was imagined as a vast cosmic canopy. The verb used to describe metaphorically how God stretched out this canopy over earth is נטה (nătăh) "stretch out," or "spread." "I made the earth, and created humankind upon it; it was my hands that stretched out the heavens, and I commanded all their host (Isa. 45:12)." In the Bible this verb is used to describe the stretching out (pitching) of a tent. Since the texts that mention the stretching out of the sky are typically drawing on creation imagery, it seems that the figure intends to suggest that the heavens are Yahweh's cosmic tent. One can imagine ancient Israelites gazing up to the stars and comparing the canopy of the sky to the roofs of the tents under which they lived. In fact, if one were to look up at the ceiling of a dark tent with small holes in the roof during the daytime, the roof, with the sunlight shining through the holes, would look very much like the night sky with all its stars. The second image of the material composition of the heavenly realm involves a firm substance. The term רקיע (răqîa'), typically translated "firmament," indicates the expanse above the earth. The root רקע means "stamp out" or "forge." The idea of a solid, forged surface fits well with Ezekiel 1 where God's throne rests upon the רקיע (răqîa') According to Genesis 1, the רקיע (răqîa') is the sphere of the celestial bodies (Gen. 1:6-8, 14-17; cf. ben Sira 43:8). It may be that some imagined the רקיע to be a firm substance on which the celestial bodies rode during their daily journeys across the sky.” - pp. 55-56 in “The Early History Of Heaven”, J. Edward Wright, Oxford University Press 2000.)

- ^ firmament (tărie) = diviziunea făcută de către Dumnezeu, conform relatării cosmogonice a așa-numitului "sacerdot" ("P" - preot) în Facere (Biblie), pentru a ține apele cosmice și a forma astfel cerul (Facere 1: 6-8). Cosmologia evreiască considera că Pământul este plat, peste el întinzându-se o tărie (firmament) în formă de boltă, sprijinită de munți și peste care se află apele cosmice. Găuri sau canale ecluzate de obloane ("jgheaburi", Facere 7: 11) permiteau acestor ape să cadă pe Pământ sub formă de ploaie. Tot firmamentul era și cerul pe care a pus Dumnezeu Soarele (Psalmi 19:4) și stelele (Facere 1 :14) în ziua a patra a facerii. Mai era o apă și sub Pământ (Facere 1 :7, 9), care în timpul Potopului s-a unit cu cea cerească pentru a acoperi uscatul. (“firmament - The division made by God, according to the P account of creation, to restrain the cosmic water and form the sky (Gen. 1: 6-8). Hebrew cosmology pictured a flat earth, over which was a dome-shaped firmament, supported above the earth by mountains, and surrounded by waters. Holes or sluices (windows, Gen. 7: 11) allowed the water to fall as rain. The firmament was the heavens in which God set the sun (Ps. 19: 4) and the stars (Gen. 1: 14) on the fourth day of the creation. There was more water under the earth (Gen. 1: 7) and during the Flood the two great oceans joined up and covered the earth; sheol was at the bottom of the earth (Isa. 14: 9; Num. 16: 30).” - How to cite this entry: “firmament”, “Dictionary of the Bible”, W. R. F. Browning, Oxford University Press, 1997. Oxford Reference Online.)

- ^ Ceea ce este descris în Facere 1:1 până în Facere 2:3 reprezintă structura universului acceptată începând din cel puțin finele mileniului II î.e.n. până în secolul IV sau III î.e.n. El reprezintă un model coerent pentru experiența omului din Mesopotamia perioadei și reflectă o viziune despre lume care explica apa care cădea din cer sub formă de ploaie sau care țâșnea din Pământ sub formă de izvoare, ca mișcarea aparentă a aștrilor pe cer. Include restricția împerecherii diferitelor specii de animale și explicația modului cum a ajuns omul să stăpânească, ceea ce pe atunci erau deja animalele domestice. Această viziune recunoaște de asemenea capacitatea omului de a schimba mediul în care trăiește. Această viziune apare în marile relatări ale facerii din Mesopotamia; aceste relatări au stat la baza reflecțiilor teologice evreiești despre creația lumii, și pe care le găsim descrise în Biblia evreiască (Vechiul Testament). Preoții și teologii evrei ai vremii care au compus cosmogonia biblică au luat în considerare ideile despre structura lumii acceptate pre atunci și au reflectat asupra lor prin prisma teologiei lor specifice și în lumina propriei lor experiențe religioase. Astfel, n-a existat niciodată un conflict între evrei și babilonieni pe tema structurii lumii, ci doar asupra celui care e responsabil de făurirea acesteia și consecințele teologice ale unei astfel de opinii. Structura în sine, ea era simplă: Pământul era considerat a fi situat în mijlocul unei imense cantități de apă, cu apă deasupra și dedesubtul acestuia. Se credea că o cupolă imensă stă așezată peste Pământ (ca un castron de sticlă întors cu fundul în sus), menținând apa de deasupra la locul ei. Pământul se credea că stă fixat pe niște fundații care pătrund adânc în adâncimile apei de dedesubt, asta asigurând că este stabil și nu plutește pe ape în voia vînturilor și valurilor. Stelele, Soarele, Luna și planetele evoluau pe traiectoriile desemnate, marcând în periplul lor de-a lungul marii bolte de deasupra lunile, sezoanele și lungimea anului. (What is described in Genesis 1:1 to 2:3 was the commonly accepted structure of the universe from at least late in the second millennium BCE to the fourth or third century BCE. It represents a coherent model for the experiences of the people of Mesopotamia through that period. It reflects a world-view that made sense of water coming from the sky and the ground as well as the regular apparent movements of the stars, sun, moon, and planets. There is a clear understanding of the restrictions on breeding between different species of animals and of the way in which human beings had gained control over what were, by then, domestic animals. There is also recognition of the ability of humans to change the environment in which they lived. This same understanding occurred also in the great creation stories of Mesopotamia; these stories formed the basis for the Jewish theological reflections of the Hebrew Scriptures concerning the creation of the world. The Jewish priests and theologians who constructed the narrative took accepted ideas about the structure of the world and reflected theologically on them in the light of their experience and faith. There was never any clash between Jewish and Babylonian people about the structure of the world, but only about who was responsible for it and its ultimate theological meaning. The envisaged structure is simple: Earth was seen as being situated in the middle of a great volume of water, with water both above and below Earth. A great dome was thought to be set above Earth (like an inverted glass bowl), maintaining the water above Earth in its place. Earth was pictured as resting on foundations that go down into the deep. These foundations secured the stability of the land as something that is not floating on the water and so could not be tossed about by wind and wave. The waters surrounding Earth were thought to have been gathered together in their place. The stars, sun, moon, and planets moved in their allotted paths across the great dome above Earth, with their movements defining the months, seasons, and year. - Citation source (MLA 7th Edition): p. 253 in "Biblical Geology." Encyclopedia of Geology. Ed. Richard C. Selley, L. Robin M. Cocks, and Ian R. Plimer. Vol. 1. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2005. pp.253-258. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 15 Sep. 2012.)

- ^ De la mit la cosmos: Primele speculații despre originea și natura lumii au îmbrăcat forma miturilor religioase. Aproape toate culturile antice au creat relatări cosmologice pentru a explica caracteristicile de bază ale cosmosului: Pământul și locuitorii lui, cerul, oceanul, Soarele, Luna și stelele. De exemplu pentru babilonieni creația universului era opera unui cuplu de zei cu trăsături umane. În cosmologia egipteană timpurie eclipsele lunare și solare erau provovate de faptul că o scroafă o mânca temporar Luna, sau un șarpe înghițea Soarele. Pentru evreii antichității, ale căror relatări cosmogonice sunt păstrate în cartea biblică a Facerii, un singur Dmnezeu a creat universul în etape succesive, într-un trecut relativ recent. Astfel de cosmologii preștiințifice conțineau cel mai adesea ideea că Pământul este plat, ca trecutul este limitat și o intervenție frecventă a zeităților sau spiritelor în ordinea cosmică, cosmosul însuși fiind constituit din stele și planete de natură diferită de aceea a Pământului. (From Myth to Cosmos: The earliest speculations about the origin and nature of the world took the form of religious myths. Almost all ancient cultures developed cosmological stories to explain the basic features of the cosmos: Earth and its inhabitants, sky, sea, sun, moon, and stars. For example, for the Babylonians, the creation of the universe was seen as born from a primeval pair of human-like gods. In early Egyptian cosmology, eclipses were explained as the moon being swallowed temporarily by a sow or as the sun being attacked by a serpent. For the early Hebrews, whose account is preserved in the biblical book of Genesis, a single God created the universe in stages within the relatively recent past. Such pre-scientific cosmologies tended to assume a flat Earth, a finite past, ongoing active interference by deities or spirits in the cosmic order, and stars and planets (visible to the naked eye only as points of light) that were different in nature from Earth. - Citation source (MLA 7th Edition), Applebaum, Wilbur. "Astronomy and Cosmology: Cosmology." Scientific Thought: In Context. Ed. K. Lee Lerner and Brenda Wilmoth Lerner. Vol. 1. Detroit: Gale, 2009. 20-31. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 15 Sep. 2012.)

- ^ În timpul perioadei celui de-al doilea Templu evreii, si mai apoi și creștinii, au început să conceapă universul în noi termeni. Modelul universului moștenit din Biblia evreiască și Orientul Mijlociu antic, în care Pământul era plat și înconjurat complet de ape, deasupra căruia se afla un regat ceresc al zeilor, care se arcuia de la un orizont la celălalt, a început să fie considerat ca învechit. În trecut, împărăția cerurilor era rezervată doar zeilor, fiind locul unde zeii determinau deznodământul tuturor evenimentelor care aveau loc pe Pământ, deciziile lor fiind irevocabile. Prăpastia care separa zeii de umanitate nu putea fi mai mare decât atât. Evoluția cosmografiei evreiești care a avut loc în perioada celui de-al doilea Templu a urmat jaloanele astronomiei elenistice. (In the course of the Second Temple Period Jews, and eventually Christians, began to describe the universe in new terms. The model of the universe inherited form the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East of a flat earth completely surrounded by water with a heavenly realm of the gods arching above from horizon to horizon became obsolete. In the past the heavenly realm was for gods only. It was the place where all events on earth were determined by the gods, and their decisions were irrevocable. The gulf between the gods and humans could not have been greater. The evolution of Jewish cosmography in the course of the Second Temple Period followed developments in Hellenistic astronomy. - “The Early History Of Heaven”, J. Edward Wright, Oxford University Press 2000, p.201)

- ^ Structura cosmografică împărtășită de această lucrare este aceea tradițională, antică, a modelului Pământului plat în care credeau majoritatea locuitorilor Orientului Apropiat și care a persistat în tradiția evreiască din cauza locului ei privilegiat în materialele religioase oficiale. (The cosmographical structure assumed by this text is the ancient, traditional flat earth model that was common throughout the Near East and that persisted in Jewish tradition because of its place in the religiously authoritative biblical materials. - “The Early History Of Heaven”, J. Edward Wright, Oxford University Press 2000, p.155.)

- ^ “Unii filozofi ai naturii spun, cu cuvinte elegante, că pământul stă nemișcat din anumite pricini: din pricina locului pe care îl ocupă în centrul universului și din pricina distanței, totdeauna egală cu marginile universului; de aceea nu poate să se încline în vreo parte; așa că rămâne neapărat nemișcat, pentru că distanța egală, pe care o are din toate părțile de jur împrejurul lui, îi face cu neputință înclinarea în vreo parte. Locul acesta din centrul universului, pe care pământul îl ocupă, nu l-a dobândit nici ca o moștenire, nici prin sine însuși, ci este locul lui firesc și necesar. Deci corpurilor grele le este proprie mișcarea înspre jos; iar josul, așa cum s-a arătat, este centrul. Să nu te minunezi, dar, dacă pământul nu cade în nici o parte; nu cade, pentru că ocupă, potrivit naturii lui, locul din mijloc. Trebuie deci neapărat ca pământul să rămână la locul său, cât timp o mișcare contrarie naturii lui nu-l dislocă. Dacă e ceva care să ți pară probabil, atunci admirația pentru faptul ăsta trebuie s-o ai pentru Cel care e izvorul acestei ordini perfecte, pentru înțelepciunea lui Dumnezeu adică.” - http://www.hexaimeron.ro/pdf/cosmologie/The-Earth.pdf

- ^ There are inquirers into nature who with a great display of words give reasons for the immobility of the earth. Placed, they say, in the middle of the universe and not being able to incline more to one side than the other because its centre is everywhere the same distance from the surface, it necessarily rests upon itself; since a weight which is everywhere equal cannot lean to either side. It is not, they go on, without reason or by chance that the earth occupies the centre of the universe. It is its natural and necessary position. As the celestial body occupies the higher extremity of space all heavy bodies, they argue, that we may suppose to have fallen from these high regions, will be carried from all directions to the centre, and the point towards which the parts are tending will evidently be the one to which the whole mass will be thrust together. If stones, wood, all terrestrial bodies, fall from above downwards, this must be the proper and natural place of the whole earth. If, on the contrary, a light body is separated from the centre, it is evident that it will ascend towards the higher regions. Thus heavy bodies move from the top to the bottom, and following this reasoning, the bottom is none other than the centre of the world. Do not then be surprised that the world never falls: it occupies the centre of the universe, its natural place. By necessity it is obliged to remain in its place, unless a movement contrary to nature should displace it. If there is anything in this system which might appear probable to you, keep your admiration for the source of such perfect order, for the wisdom of God. Grand phenomena do not strike us the less when we have discovered something of their wonderful mechanism. Is it otherwise here? At all events let us prefer the simplicity of faith to the demonstrations of reason. (Basil the Great, Nine Homilies on the Hexameron, Homily I, paragraph 10, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/32011.htm )

- ^ Și ceea ce s-a întâmplat mai târziu era mai puțin și rar; de exemplu, când "soarele s-a oprit pe loc și a luat-o în direcție opusă." Ori asta constatăm că s-a întâmplat și în cazul nostru. Pentru că și în vremea noastră, în cazul celui care a depășit limitele necredinței, mă refer la Iulian, multe lucruri stranii s-au întâmplat. Astfel, când evreii au încercat să ridice din nou Templul în Ierusalim, au izbucnit flăcările din temelii, împiedicându-i să pună piatră pe piatră. (And what took place at a later period were few and at intervals; for example, when the sun stood still in its course, and started back in the opposite direction. And this one may see to have occurred in our case also. For so even in our generation, in the instance of him who surpassed all in ungodliness, I mean Julian, many strange things happened. Thus when the Jews were attempting to raise up again the temple at Jerusalem, fire burst out from the foundations, and utterly hindered them all. (Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, Volume X, Edited by Philip Schaff, first published in 1888; Cosimo 2007, “Homilies Of St John Chrysostom on the Gospel of Matthew”, Homily IV, p.21.))

- ^ Pentru că El nu numai că le-a făcut, dar le-a zidit și cu tot ce le trebuia ca să-și îndeplinească, fiecare, rostul lor, nepermițându-le să fie toate imobile, nici tuturor să fie mobile. Cerul, de exemplu, a rămas fix și imobil, după cum profetul spune: Și a pus El cerul ca o boltă, și l-a întins ca pe un cort peste Pământ (Isaia 40:42). Dar pe de altă parte, Soarele și restul stelelor se mișcă pe traiectoria lor în fiecare zi. Și iar, Pământul stă (imobil), dar apele sunt în continuă mișcare. (For He not only made it, but provided also that when it was made, it should carry on its operations; not permitting it to be all immoveable, nor commanding it to be all in a state of motion. The heaven, for instance, has remained immoveable, according as the prophet says, He placed the heaven as a vault, and stretched it out as a tent over the earth. Isaiah 40:42 But, on the other hand, the sun with the rest of the stars, runs on his course through every day. And again, the earth is fixed, but the waters are continually in motion; […] - Catholic Encyclopaedia, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/190112.htm )

- ^ Dar cine i-a dat mișcare în primul rând? Și mai ales ce-l mișcă pe traiectoria lui, deși defel statornic și nemișcat, de-a dreptul neobosit și dătător și susținător de viață, și toate titlurile pe care i le-au dat poeții, că niciodată stând și niciodată nelipsindu-ne de binefacerile lui. Cum reușește el să facă ziua când e deasupra Pământului, și noaptea când e dedesubt? (But who gave him motion at first? And what is it which ever moves him in his circuit, though in his nature stable and immovable, truly unwearied, and the giver and sustainer of life, and all the rest of the titles which the poets justly sing of him, and never resting in his course or his benefits? How comes he to be the creator of day when above the earth, and of night when below it? - Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Philip Schaff, Christian Classics Ethereal Library, http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf207.iii.xiv.html )

- ^ Căci dacă e adevărat ce spui, și de asemenea că bolta cerească se prelungește neîntrerupt de învăluie totul în ea, și dacă Pământul și împrejurimile lui sunt puse în mijloc, și dacă mișcarea tuturor corpurilor cerești se face rotindu-se în jurul acestui centru fix și tare […]. (“For if it is true, what you say, and also that the vault of heaven prolongs itself so uninterruptedly that it encircles all things with itself, and that the earth and its surroundings are poised in the middle, and that the motion of all the revolving bodies is round this fixed and solid centre, […]” - St. Gregory of Nyssa, On the Soul and Resurrection, Catholic Encyclopaedia, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/2915.htm )

- ^ Nici 30 de ani mai târziu, totuși, Hrisostom spune răspicat că referirea (din Iezechiel 28:18) trebuie să fie la un om (și nu la o ființă cerească). Dar Gură-de-Aur, ca și Pavel de Samosata, e un teolog al Antiohului, și toți sirienii caută să adopte înțelesul literal al Scripturii, evitând alegoria. (Not thirty years later, however, Chrysostom says bluntly that the reference must be to a man. But then Chrysostom, like Paul of Samosata, belonged to Antioch, and all Syrians tended to look for the literal meaning of the text of Scripture, and to eschew allegorism. - The Fourth Century Greek Fathers as Exegetes. W. Telfer. The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 50, No. 2 (Apr., 1957), pp. 91-105. Published by: Cambridge University Presson behalf of the Harvard Divinity School.)

- ^ Dar când privești nu pietricica ci Pământul tot purtat peste ape și nu scufundat sub ele, admiră puterea Lui care a făcut aceste lucruri minunate cu puterea lui supranaturală! Dar de unde vine ideea asta, că Pământul este susținut deasupra apelor? Profetul o declară când ne spune: "Lui care a pus Pământul peste mări și l-a fixat peste adâncuri." Și iar: "Lui care a zidit Pământul peste ape." Ce spui tu? Că apele nu-s capabile să poarte deasupra o pietricică, dar poartă ele Pământul tot, mare cum e; și munții, și colinele, și urbele, și plantele, și oamenii, și fiarele; și încă nu-i scufundat! ("When therefore thou beholdest not a small pebble, but the whole earth borne upon the waters, and not submerged, admire the power of Him who wrought these marvellous things in a supernatural manner! And whence does this appear, that the earth is borne upon the waters? The prophet declares this when he says, "He hath founded it upon the seas, and prepared it upon the floods."1416 And again: "To him who hath founded the earth upon the waters."1417 What sayest thou? The water is not able to support a small pebble on its surface, and yet bears up the earth, great as it is; and mountains, and hills, and cities, and plants, and men, and brutes; and it is not submerged!" - St. John Chrysostom, Homilies Concerning the Statutes, Homily IX, paras.7-8, in A Select Library Of The Nicene And Post-Nicene Fathers Of The Christian Church, Series I, Vol IX, ed. Philip Schaff, D.D.,LL.D., American reprint of the Edinburgh edition (1978), W.B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.,Grand Rapids, MI, pp.403-404.

- ^ Flat Earth - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- ^ Flat Earth - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- ^ Lactanțiu care a trăit cu un secol înaintea lui, s-a apucat să demoleze concepția privitoare la sfericitatea Pământului, acțiune încununată cu un succes răsunător. Cel de-al treilea volum al lucrării sale Instituții Divine, este intitulat Despre Falsa Înțelepciune a Filozofilor și conține toată argumentația naivă împotriva existenței antipozilor, cum ar fi că oamenii nu pot merge cu picioarele deasupra capetelor, că ploaia și zăpada nu pot cădea în sus, argumente care nu puteau fi utilizate cu șapte sute de ani mai înainte de vreo persoană cultivată fără să apară drept nebun. Forma sferică a Pământului și existența antipozilor n-au mai fost restaurate decât spre sfârșitul secolului al IX-lea, la 15 secole după Pitagora. Cosmologia acestei perioade se întoarce direct la babilonieni și la evrei, fiind dominată de două idei principale: că Pământul are forma Sfântului Tabernacul și că firmamentul este înconjurat de apă. Ultima idee e bazată pe Facere 1:6-7. Din aceasta s-a dedus că apele din ceruri au rămas pe acoperișul firmamentului, scopul lor fiind, așa cum explica Vasile cel Mare, să protejeze lumea împotriva focului ceresc. “Lunaticii - Evoluția Concepției despre Univers de la Pitagora la Newton”, Arthur Koestler (p.e. 1959), Humanitas 1995, pp.76-77.

- ^ Într-adevăr, din secolul al V-lea pâna la finele secolului al IX-lea, anumiți Părinți ai bisericii timpurii precum Sfântul Ieronim sau călugărul Cosmas susțineau că Pământul și firmamentul stelelor avea forma unui tabernacul dreptunghiular. Nu s-a mai crezut din nou că Pământul este rotund, decât din secolul al IX-lea încolo, odată cu scrierile călugărului Bede Venerabilul. (Indeed, from the fifth century until the end of the ninth century, Earth and the firmament of the stars were thought by some church fathers such as St. Jerome and the monk Cosmas to be shaped like a holy tent or rectangular tabernacle. It was not until the end of the ninth century that the monk the Venerable Bede (673-735) stated that Earth was believed to be spherical again. - (Astronomy And Cosmology: Geocentric And Heliocentric Models Of The Universe, Scientific Thought: In Context, Anna Marie Eleanor Roos, Ed. K. Lee Lerner and Brenda Wilmoth Lerner. Vol. 1. Detroit: Gale, 2009. p32-42.)

- ^ Pasajul din Isaia 40:22 care se referea la "cercul pământului" și la "cerurile întinse ca un cort", au contribuit și ele la credința creștinilor că Pământul este plat. (The reference in Isaiah 40.22 to the 'circle of the earth' and to 'the heavens as stretched out like a tent', also contributed to the early Christian belief in a flat earth. - Sphere or Disc? Allusions to the Shape of the Earth in Some Twelfth-Century and Thirteenth-Century Vernacular French Works. Author(s): Jill Tattersall, Source: The Modern Language Review, Vol. 76, No. 1 (Jan., 1981). pp. 31-46. Published by: Modern Humanities Research Association.)

- ^ Historia Naturalis a lui Pliniu a devenit foarte cunoscută prin împrumuturile lui Solinius (secolul al III-lea d.H.), al cărui Collectanea rerum mirabilium a fost abuzată la rândul ei de către episcopul de Sevilia, Isidor, în secolul al VII-lea. Opinia lui Isidor în privința formei Pământului e dificil de determinat. Despre "Etimologia" lui, pe larg folosită și citată în scrierile din epoca Cruciadei, G.H.T. Kimble remarcă: "Apare suspiciunea că … Isidor copiază ceva ce nu pricepe complet." În atari condiții cu greu poate să fie de mirare că și compilările medievale ulterioare bazate pe scrierile lui Isidor au moștenit și ele neclaritatea episcopului. Enciclopediștii medievali au fost totuși de acord în general că Universul era o sferă în al cărui centru se afla Pământul. Uneori se făcea comparația (ca în De Imagine Mundi) cu un ou: coaja reprezenta cerul, albușul era eterul, gălbenușul era atmosfera, iar "picătura de grăsime"din centru (sămânța) era Pământul. Asta nu presupune însă deloc un Pământ sferic, căci înainte de toate este vorba despre o imagine. (Pliny's Historia naturalis became widely known through the borrowings of Solinus (third century A.D.), whose Collectanea rerum mirabilium was in turn plundered by the seventh-century Bishop Isidore of Seville. Isidore's views on the shape of the earth are difficult to pin down. Of his Etymologiae, widely used and quoted in writings of the Crusade period, G. H. T. Kimble remarks that 'the suspicion is aroused that... he is copying something he does not fully understand'. It is hardly surprising that later medieval compilations partly based on Isidore should inherit his haziness. Medieval encyclopaedists were, however, generally agreed that the Universe was a sphere, with the earth lying at its centre. A comparison was sometimes drawn (as in the De Imagine Mundi) with an egg: the shell represented the heavens, the white the ether, the yolk the atmosphere, and the 'fat drop' in the centre (the germ) the earth. This does not absolutely presuppose a spherical earth, for it is above all an image. - Sphere or Disc? Allusions to the Shape of the Earth in Some Twelfth-Century and Thirteenth-Century Vernacular French Works, Author(s): Jill Tattersall, Source: The Modern Language Review, Vol. 76, No. 1 (Jan., 1981), pp. 31-46, Published by: Modern Humanities Research Association.

- ^ Ca și Midrașul și Talmudul, Targumul nu consideră nici el că Pământul este un glob sau de formă sferică, în jurul căruia se rotește Soarele într-un ciclu complet în 24 de ore, ci că este un disc plat, peste care Soarele își completează semicercul într-o medie orară de 12 ore. (Like the Midrash and the Talmud, the Targum does not think of a globe of the spherical earth, around which the sun revolves in 24 hours, but of a flat disk of the earth, above which the sun completes its semicircle in an average of 12 hours. (The Distribution of Land and Sea on the Earth's Surface According to Hebrew Sources, Solomon Gandz, Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research, Vol. 22 (1953), pp. 23-53, published by American Academy for Jewish Research.

- ^ The ancient Israelites inherited views of the universe from their Canaanite ancestors and then transformed these views to accord with their particular theologies. The tradents of the Hebrew Bible took theses traditions and further refined them to fit a strictly monotheistic theology. The Jews of the Greco-Roman period faced a dilemma: the model of the heavenly realm they inherited from the biblical materials was becoming obsolete as they learned the newer Greek models of the cosmos. Jewish texts and artifacts of the Greco-Roman period indicate that while some were content with the traditional view of the heavens inherited from the Bible, others had abandoned the biblical traditions in favor of the Greek models of the universe. While it has been fashionable to state that Jewish religious ideas developed significantly during the so-called Babylonian Exile (ca.586-539BCE), it is more accurate to say that Judaism changed most in the wake of Alexander the Great's conquests (333-32 3BCE) as Hellenistic culture increasingly began to transform Israelite and other ancient Near Eastern cultures. This is no more clearly evident than in their cosmic speculations. The ancient Near Eastern three-tiered universe (heaven-earth-netherworld) was largely displaced by models of the cosmos in which the earth is surround by several heavenly spheres. Some Jews transformed the biblical depictions of the universe to fit these newer models; consequently, they shaped how people would depict the universe for well over a millennium. This is an important aspect of Western cultural history, and it is hoped that this volume will provide further insight into the origins and early development of Western views of the heavenly realms. […] Even the later rabbis, traditionalists to be sure, adopted a model of the universe that was more Hellenistic than biblical. The earliest Christians also depicted the universe in Hellenistic fashion. When Christianity became the religion of the empire, the state became the enforcer of theological and scientific orthodoxy. Variety in the depictions of the universe began to disappear. - The Early History Of Heaven, J. Edward Wright, Oxford University Press 2000, p. X (Preface)

- ^ The revival of Aristotle in the medieval Latin West prompted scholars like Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) to construe theology by analogy with Aristotelian science. Even so, in the context of medieval society, the definitive resolution of anomalies in the understanding of the cosmos was impossible and hence generated a resignation to the limitations of human knowledge. Nicholas Oresme (1320-1382) took seriously the hypothesis of the diurnal rotation of the earth but rejected it because no confirmation seemed possible; he fell back on the Bible in this case as providing persuasive confirmation of the greater probability of the geocentric view. - How to cite this entry: André L. Goddu, "Science and the Bible.", The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Bruce M. Metzger and Michael D. Coogan, eds. Oxford University Press Inc. 1993. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Ptolemy applied the theory of epicycles to compile a systematic account of Greek astronomy. He elaborated theories for each of the planets, as well as for the Sun and Moon. […] It essentially molded astronomy for the next millennium and a half. - To cite this page, MLA Style: "physical science." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 15 Sep. 2012.

- ^ When Christianity became the religion of the empire, the state became the enforcer of theological and scientific orthodoxy. Variety in the depictions of the universe began to disappear. There remained, both in the religious as well as in the scientific community, those voices proposing alternate models. - The Early History Of Heaven, J. Edward Wright, Oxford University Press 2000, p.X, Preface

- ^ Revoluția produsă de Copernic a schimbat cosmologia occidentală. Consensul științific universal este că Pământul se rotește în jurul Soarelui, fapt susținut de legile fizicii și o substanțială cantitate de observații. Și totuși, în Statele Unite contemporane, aproximativ o cincime a populației încă mai crede că Soarele se rotește în jurul Pământului. Articolul care urmează pune acest fapt statistic în contextul lui social, citând lipsa de educație științifică solidă ca factor explicativ predominant. (The Copernican Revolution changed Western cosmology. The universal scientific consensus is that Earth orbits the sun - a fact backed up by the modern laws of physics and substantial observational evidence. However, in the United States today about one-fifth of residents think the sun goes around Earth. The following article puts that statistic in its social context, citing lack of consistent science education as a predominant factor. - Astronomy and Cosmology: Geocentric and Heliocentric Models of the Universe. Anna Marie Eleanor Roos, Scientific Thought: In Context, Eds. Brenda Lerner and K. Lerner, Vol.1, Detroit, 2009. p32-42, 3 vols. Full Text COPYRIGHT 2009 Gale, Cengage Learning.)

- ^ în 2009, 4 din 10 romani cred ca Soarele se învârte în jurul Pământului: http://www.romanialibera.ro/actualitate/educatie/42-dintre-romani-cred-ca-soarele-se-invarte-in-jurul-pamantului-195191.html Arhivat în , la Wayback Machine. http://www.ziare.com/social/romani/4-din-10-romani-cred-ca-soarele-se-invarte-in-jurul-pamantului-1032389